- Home

- Maurilia Meehan

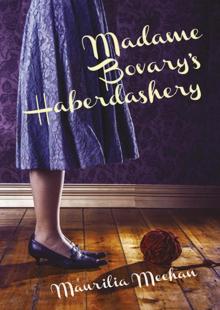

Madame Bovary's Haberdashery Page 2

Madame Bovary's Haberdashery Read online

Page 2

‘Crying makes me feel good. If I don’t cry, I make myself cry. In fact I haven’t cried yet this week …’

Her pulse quickened. She put down the iron, turned off the power. She wanted to get this right.

‘Come here,’ she whispered.

He stood up, accepting this peace gesture.

As he took a step towards her, she held her breath. Kicked him violently in the shins. With her metal capped, pointed, biker-buckled fur-lined Italian boots.

Tears welled in his eyes.

‘Say thank you,’ she said.

Leaving Erica’s house for the last time after that totally undeserved kick, Zac had decided to quit Inner Calm and join Inner Savage, which he knew met for darts at the New Criterion.

Stepping into the darkened street, he had found it appropriate that it was raining and that he was without a raincoat. Even Mother Nature was against him.

Not anxious to get back to his mother’s Bible reading and chamomile tea, he decided to revel in his wretchedness and walk the long way home. Via the New Criterion.

As he walked along the rainswept streets, lovers sharing umbrellas bumped into him. He shins still throbbed and his lower back began to ache. To distract himself from his lonely pain, he tried to add up all the women he had ever been with, along with their individual erotic theme songs, but lost count. He must be working too hard over his masterpiece.

Perhaps he should continue the yoga he had started at Inner Calm. Why could he not succeed in controlling his restless mind? Yoga had helped him, at least in terms of flexibility, but his mind had rebelled against the meditation session at the end, when they were urged to still their minds. He didn’t want to. He couldn’t imagine his mind not full of women and Flaubert and his own glorious literary future.

A seductive sound, familiar and yet strange, stopped him in his tracks.

Where was he?

He did not recognise this dark inner-city street. It certainly was not the way to the darts club. And there was that sound again.

What was it, if not an angel laughing?

Odette

On the other side of the road he saw a thin young woman, her blonde hair lit up like a halo by the lights from the art gallery windows behind her. She was arching backwards, like the woman in his Japanese screen painting, her whole body shaking with that irresistible laughter.

She was clearly a queen bee, surrounded by a circle of admiring drones, the star of whatever happening was taking place at the gallery. And even from across the road he could see, by her quick muscled movements, that this perfectly whittled woman had that type of nervous tension that could only be settled with his type of sex. He could assuage it, he would know her erotic melody, have her resting peacefully in his arms by dawn.

He crossed the road.

Joined the other men who were following her like a bridal train as she moved inside the gallery.

Inside, he squinted, inspecting the darkened space.

There seemed to have been some kind of accident. Shards of pots littered the shelves. He could see only two intact pots among the ruins. Careful eavesdropping informed him that it was the smashed remains themselves that were causing all the excitement. In one corner, a grainy film which looked like security footage was playing. Over and over, it showed a shadowy figure smashing pots with a hammer.

Systematically edging closer to her through the drunken crowd, he watched her waving her wineglass around, delighting in being the centre of attention. Those perfect, high cheekbones, like angel’s wings. Those taut muscled arms and legs exposed by her flimsy, summer chiffon. Didn’t she feel the cold?

Finally Zac managed to corner her, blocking her way as the rest of the crowd suddenly rushed towards a new batch of hot finger food. She laughed as he apparently fell against her, then righted himself, though all his senses strained towards her.

‘I understand it’s art,’ he said, his eyes resting on her bare shoulders, ‘but why the smashed pots?’

When she leaned forward like that, was she aware that he could see her small, high breasts? She was not wearing a bra. She was so relaxed in her own skin, bien dans sa peau, as the French said, as he knew that he would never be.

He was not able to hear her reply over the drunken din around them, so he just nodded understandingly, until her heavenly lips stopped moving, formed an expectant smile. She held his gaze, then, in silence.

This man’s eyes intrigued her. She recognised in their depths that exact shade of azure that she had so recently failed to achieve in her last batch of glaze.

Which had inspired, or so she believed, her disgust with this exhibition and the attack upon it the night before. Caressing the small pink-handled hammer in her coat pocket, Odette had secretly entered the deserted gallery.

Her twenty glazed ceramic pots were subtly displayed under green and purple lights, ready for the opening next day. Passing her own poster on the glass door, not pausing at the wine goblets and bottles of Swords’ wine lined up on tables, she had advanced.

She had never been clumsy, never broken things by accident, and her movements now, from pot to pot, were methodical. She would have told anyone who had asked that it was because of that failed glaze. But was this the real reason for her actions?

Odette had never been to a therapist. At art school, one didn’t. Self-analysis was the enemy, waiting to kill off their fitful artistic impulses. Odette, lurching unreflectingly from one style to the next, one man to the next, saw herself as living in wild freedom, just like any male artist. Above all, she did not want to be tied down.

All the boys knew that it was dangerous to go out with Odette, because she always dumped you first. Parties, social drugs and most of all, a new man in her bed were her reliable cures for boredom. She interspersed half-crazed boys with fairly conservative men, who she found easier to confound.

She remained unaware that her deepest fear was that of failing to amuse. Of seeing in others that expression of boredom which she remembered in her parents’ eyes. She was the youngest of six children, born to parents too old and too tired to have greeted her arrival with anything but sighs. A new sacrifice to be offered up to the Lord.

She had learned early that the way to get their attention had been to develop eccentricities. At age three she had professed a liking for raw cauliflower, and everyone had watched her as she had chomped determinedly through it. She had worn her brothers’ hand-me-downs, refusing her sisters’.

Apparently sound kitchen chairs collapsed under her.

Any bowl she ate from broke in her hands.

Angry eyes stayed on her when she broke things. Becoming the annoying one in the family, though self-destructive, was far better than being the ignored one.

One rainy day, after she had cut off all her blonde hair, her older sister had told Odette, with some satisfaction, why she was not normal.

‘Mum told me not to tell you that she dropped you on your head when you were a baby.’

Her sister touched Odette above her left temple.

‘See? Right there …’

Odette rubbed at the spot. It was numb.

Later she would charge the girls at school a dollar to stick a pin in it until it bled.

Her temperament was thus established.

Now, as she sneaked into the gallery with a torch, she was aware only of being consumed with the desire to break each ceramic piece with the small pink hammer. Such impulses, she believed, were part of being wild and brave.

In fact, she was predictably following a neural pathway gouged out long ago. She moved along her endless earthen furrow, inside its protective walls, the world outside muffled and distant. She was safe, but also ignored – unless she made a lot of noise. Her apparently heightened life registered on her own nerves as being quite unexceptional.

Some part inside her was just as numb as that spot on her forehead.

After he had discovered the wreckage in the gallery at nine o’clock the next morning, the gallery owner had

phoned her.

‘Darling Odette, you really are most annoying. Do you actually want to stay Fringe?’

After much frenzied thought he had come up with a strategy. The exhibition would go ahead as planned that afternoon. He would screen the security video in a loop. Performance art.

‘The genius po-mo potter smashing her own work darling. Just enough time to print out stills of each broken piece for sale.’

The two remaining intact pots would, of course, soar in value.

‘But you must promise to turn up darling, to sign the prints.’

Impressed by his twisted mind, Odette had agreed.

And together they turned breaking things into an art form.

When, hand-in-hand, Zac and Odette left the gallery and went out into the darkened street, he was surprised to see that the cafés were still open. It seemed to him that eons had passed since he had met her, but in truth it was not yet midnight.

She must know that trendy area well, but she led him to a twee tea shop that looked as if it belonged on a film set. Zac, a suburban man at heart, wondered if the waitress, dressed demurely in black with a frilly white apron, was really a man. There must be some twist.

Conversation was refreshing, easy, unlike Zac’s recent tortuous experience with Erica. He and Odette discussed the relative merits of black, green and white teas, and whether the famed English Brown Betty teapot that the café used could really improve the flavour of tea. Odette thought so, and he deferred to her, the ceramic artist.

Perhaps there was no twist?

When the cups were cleared away, Odette produced a battered pack of Tarot cards and spread them out on the starched white cloth. She muttered in a singsong way as she turned the cards over.

‘Carl Jung thought that the Tarot cards call upon our individual unconscious …’ he ventured.

She did not look up.

‘And Plato based his philosophy, which we like to think of as rational, on Eastern mysticism …’

But she was still giving her whole attention to the cards, and he petered out again, watching her for a few more moments before blurting out, ‘What exactly are you asking the cards?’

Now she looked up.

‘Whether I should take you home or not.’

Great expectations

During those first blissful months with Odette, Zac would emerge from his writerly toil behind his Japanese screen and present different versions of his work for Odette and Cicely to consider.

When Rodolphe abandons Emma, should it be no matter, she was a pretty mistress or all the same she was a pretty mistress?

Odette loved to listen to the cultivated precision of his words – though the exact meaning of his sonorous flow often escaped her. And Cicely, though a voracious reader, did not read much French.

Thus, Zac could be confident that they were both impressed by the sophistication of his foreign language skills. Through sharing his work with them, Zac expected the women to also share his love of Flaubert. Tall, full-bodied, with a large handlebar moustache, he had never married. In all four ways he resembled Zac.

But they preferred to dwell on Rodolphe, the handsome, heartless roué. Wasn’t he the one who had started Emma Bovary’s downward spiral? Mais non! Zac’s thesis was that the real villain was not Rodolphe but M. Lheureux, the money lender who tantalised Emma with Paris fashions on the never-never. Flaubert’s novel brilliantly foreshadowed the rise of consumer culture and the role of the international bankers.

At least, that was half of Zac’s thesis.

Cicely had opinions, but she kept them to herself.

She believed that what Emma Bovary actually wanted, indeed, what all women who fainted and had nervous trouble wanted, was simply a little control over her own life. With her own credit card and a job in a draper’s shop, Emma would not have needed to dream of rescue by Rodolphe. In fact a seducer such as he would never have chosen her. He would have kept circulating, a blowfly looking for defenceless, easy meat. Emma Bovary, successful shopkeeper, would not have appealed to him.

Cicely had touched on this topic in her small novel, Last Chance, modestly reviewed. She had even been nervously interviewed. She had given a copy to Odette ages ago, but was still waiting for a comment from her. She had seen her pass it on to Zac, of course, who had turned out to be this intimidating Flaubert scholar. So Cicely had taken his similar lack of response as polite dismissal of her slim volume.

What was the other half of Zac’s thesis?

Well, the novel showed, more than anything else he had ever read, the truth about women. And the irony was that none of the string of women Zac had lived with, discussed the novel with, realised it.

The first truth about women, which Flaubert had made clear by giving Emma an adoring husband (for him the universe expanded not beyond the silken circuit of her petticoat) whom she unaccountably loathed, was this:

No matter what you did for women, they were never satisfied.

The second truth:

Women bled men dry, if given the chance.

The history of Zac’s own domestic arrangements was informed by this philosophy. While he spent his years translating the great work, he had always preferred women to take care of the financial side of things. This was not unfair. For his part, he offered much – he was a modern stay-at-home house-husband, a type much in vogue. There was nothing he enjoyed more than housework after a hard day at the desk, and he especially loved the rasp of sharpening knives.

Pity about Cicely’s knife phobia.

Pity too that neither of these women had a proper job.

True, Odette went out each day to her dusty studio at Northcote Potteries, which she had, gratis, in return for a few hours each week demonstrating ceramic techniques.

And Cicely seemed to eke out a living selling the woolly jumpers she was always fabricating from those annoying mounds and tangles of wool that were lying around the house, tripping him up. Zac had successfully blanked out the possibility that she might have actually sold copies of her so-called novel.

However, all was not lost. Any day now he was due to inherit not one but two properties from an ailing great-aunt, who was dying rich, it seemed, in spite of having spent her life in Africa as an Evangelical missionary. One was a beachside property in Nigeria. The other was a brand-new flat in Docklands.

From the aunt’s dodgy lawyer, he had already obtained and duplicated the Docklands inspection key.

And he was also borrowing hugely from him, in view of his great expectations.

Ménage à trois?

For weeks, Cicely had distantly orbited the planet of love and exhilaration which Zac and Odette had created.

Then the universe realigned itself in a cataclysmic way.

One night, after Zac had absentmindedly undressed in the dark, and slid under the sheets, he found himself lying next to a much plumper, warmer body.

In the movies, and the old novels, the man doesn’t realise that someone else has taken his lover’s place. Zac had known straight away of course, because Cicely smelled of warm chocolate cake, and, he soon found, tasted similarly. His lust told him not to let on, not to interrupt the ponderous, cautious rhythm that he was hoping would eventually escalate, would lead to the high C that would make it all worthwhile--a Nessun’ Dorma no less …

But just as a crescendo was surely nigh, Cicely stiffened, holding back from him. Different as her energy was from the explosive Odette’s, Cicely had been, at last, going to come, when, abruptly, she pulled away from him. Why was she resisting being carried away on that wave that, once started, he had thought, was irresistible?

This was a first for Zac. He was Captain Midnight, a masterful lover, but it put him off his stroke. What could have gone so disastrously wrong?

He was about to ask her, but she moved quickly and her practised, oiled hands were making speech impossible. But he did not like to come – ah the French jouir was so much more delicate – alone. So it was his turn to pull away from her.

/>

Zac kept a tight hold of her hand to stop her leaving, as, sighing, they both turned onto their backs. Listening to the wind rattling the window. Pretending to sleep.

Until, again without warning, she sat bolt upright in bed, turned on the lamp and began frantically searching the bed, running her hands over the sheets, making him move so that she could check under him. Seeming satisfied, she turned off the light and, cautiously got back into bed.

‘What was that all about?’

‘Spiders.’

Cicely, it emerged, under Zac’s determined questioning, was riven with more complexes than just a fear of sharp knives. This time it was white-tailed spiders in the folds of the bedsheets. Rational Zac always attributed such aversions to childhood trauma. One of his favourite things about sleeping with women was the way it freed them up, and he was anticipating a juicy revelation from Cicely at this point.

‘Something nasty happened in the woodshed to little Cicely?’

Other women had found his method of enquiry funny, but there was only a tense silence.

‘I’m serious. If one bites you on the finger, your whole arm from the elbow down turns white and rots and has to be amputated.’

So, no explicatory rubber ducky stories from Cicely after all. Far from it. She went on to warn him about sneezing.

‘You should always sit or stand with your back perfectly straight, otherwise a sneeze can injure your spine.’

About the hairdresser.

‘Never lean your head back too far in the washbasin or you could burst a main artery in the neck. Do men lean back? Anyway it’s been in the paper. Hairdresser syndrome.’

She paused.

‘About before. It’s not you. It’s …’

He groaned.

‘No it’s true. Look, I used to come all the time. So easily it was almost embarrassing. I still go off every time I squeeze my legs together if I’m not careful.’

‘Er … multiple orgasms?’

Was he becoming a hopeless lover?

‘But last time I was with someone, in the middle of my usual, all of a sudden I saw a huge white-tail crawling out from between my thighs …’

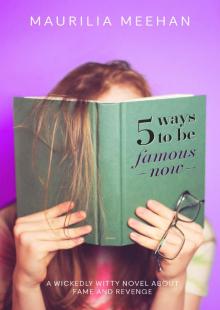

5 Ways to be Famous Now

5 Ways to be Famous Now Madame Bovary's Haberdashery

Madame Bovary's Haberdashery