- Home

- Maurilia Meehan

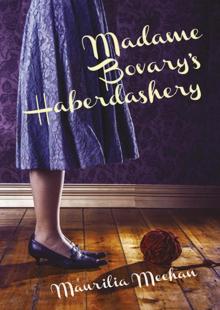

Madame Bovary's Haberdashery Page 5

Madame Bovary's Haberdashery Read online

Page 5

Weeks later, when Cicely had actually rung, Zac had picked up.

‘How did you get this number? She doesn’t want to speak to you. Just accept it. You’ve lost her … after what you wrote in your novel, what do you expect? You stole her life, like you stole my ideas …’

‘What ideas?’

‘You know. Anyway, she’ll be busy working on our act …’

‘The knife-throwing?’

‘She’s a great target woman. Fearless. And we’re doing the disappearing woman …’

Cicely saw a golden casket into which Odette was stepping, yes, fearlessly, dressed in a glittering swimsuit …

‘The woman tied up and locked in a casket who disappears …?’

‘For good.’

The line had gone dead.

Having given up on the phone, she turned to sending unanswered emails into the ether, though to read the screen now she had to tape a magnifying sheet over it.

She was afraid to go to the optometrist in case, as she feared, she was gradually going blind.

As the months passed, the greengage plums outside her window ripened, but Cicely was too slow and, overnight, the tree was stripped of fruit. Thieves everywhere, she reflected.

She had made no attempt to meet any of her neighbours. Cicely told herself that her solitude suited her. She no longer had to make the effort to be chatty over the breakfast table with the new Odette and Zac. Not, of course, that they would have been talking to her anyway, if they had been still living together.

She led a lazier, paler life now, sitting for hours in her chintz armchair, resting her eyes, dreamily escaping into second-hand lives through Talking Books. She told herself that she should be grateful. She could do as she pleased.

And mercifully, there were no witnesses to her new magnifying glass and other props to sight. She did not have to hide what would be noted by others as disability aids, the latest being the sunglasses that she had to wear indoors because of the glare from the windows. And she was free to spill sugar or drop cups without being observed, to hack away with the blunt knife without Zac harping on at her to let him sharpen it.

What was it about men and sharp knives anyway? She remembered that scene in the kitchen and shuddered again.

No one either to notice that the library’s small supply of literary Talking Books had been quickly exhausted and that, to her surprise, Cicely now found herself having a hoot with the lady detectives. Agatha Christie, it seemed, was endless on Talking Books.

Better this privacy, she told herself, than hearing Zac comment on her new, lowbrow taste, or watch him straighten up things she had knocked over, redo the dishes she had just washed. And that was of course, the good old days before …

And she could now return to her writing. Her old publisher, Foxy, had been devoured by Mastiff Inc, however, and though they were keen for the follow-up that Cicely had been signed for so cheaply, the contract was conditional. She tried to put out of her mind that she now had to lose weight and obtain a Media Awareness Certificate if she was ever to fulfil the terms of her new contract.

With her failing eyesight, she could no longer rely on her handiwork for income, and this cheap flat, her only shelter, would be torn down at the end of the year. More threatened than ever by fearsome financial thoughts, she at last started to organise her work space. Her huge Jurassic computer was waiting for her, sitting on a table in her study, with the A4 magnifying sheet taped over the screen. As slowly as possible, she shuffled folders, arranged books and pens around it.

On the wall above her table, where, in her youth – for, approaching forty, she feared the best was behind her – she would once have placed a portrait of a mournful Virginia Woolf, she now placed a photo of Agatha Christie. Having read the biographies of both women, she had been left envying the joyful, varied life of Agatha, rather than the angst-ridden fate of Woolf.

This photo showed Agatha working in the deserts of Mesopotamia at the archaeological digs that she used to go on with her much younger and adoring second husband, Max Mallowan. And, who knew, Agatha Christie’s warm eyes, looking down on her as she worked, might act as a charm … whereas Woolf would be in no state to help anyone.

Cicely then unearthed her special pen with its built-in light, and took it into the bedroom, along with her tattered blue notebook. Though she would soon no longer be able to see well enough to reach out in the dark and capture her thought bubbles as they arose, she placed these two items on the bedside table anyway, as talismans.

On that table she had already placed in a heart-shaped crocheted frame – a present from Miss Ball – a photo which she had kept hidden in a drawer in the old house.

She knew that normal adults put photos of family, lovers, perhaps even pets, by their bedsides, and that only a teenager would cut out a picture from a writerly magazine of a man she had never met, and put him in a crocheted, heart-shaped frame by her bed. But even as a child, her fantasy world of books had been her secret armour, protecting her from her mother’s whining complaints, and the convent school, where Sister Whacko had ruled hell.

Her heart warmed now as she gazed at the brooding, craggy good looks of the man holding a black cat in his arms. Cicely had long had a crush on this man and now here he was, out in the open at last, next to her pillow. Normal for him, a European, to accept the manner in which a twosome may become a threesome. Or vice versa. Yes, Milan Kundera spoke to her, understood the ‘unbearable lightness of being’ caused by the sudden termination of a relationship. She dreamt of him, as she slept with the Dutch Wife which Odette had mocked. Which Cicely, privately, called her Czech Husband.

She had eyed with distaste the cold, plastic sex toy that Odette had bought her for her last birthday. It was as unappealing to Cicely as a green, astringent, unripe banana would have been to her palate.

It would need to be ripened by her fertile, romantic imagination, by an intimate story, such as those in her dream world. For when she fell asleep, hugging her pillow tightly, embracing it between clenched thighs, shadowy sleep wove its spell, and she awoke, contented, though her Catholic mind censored the lurid detail of her erotic dreams of Milan.

Lately, however, she had been falling asleep warily.

Especially since that visit to Northcote Potteries.

Expecting to surprise Odette at work, she had instead found the studio was empty except for a rather attractive young man with a shock of black hair who was washing the skirting boards.

‘Her friend came by with her key and took all her stuff in his van. Fattish guy with a big moustache …’

‘What did he say?’

‘Not a word. Not too friendly.’

Yes, lately, Cicely’s sleep had been fitful. Her dreams were now of Zac’s glinting ruby-handled daggers, pinning Odette to the wall. Of a golden magician’s casket into which Odette stepped.

Too fearlessly.

Until, finally, Cicely determined to arrive at the Docklands apartment.

Unannounced.

A bit of rejigging

To ward off strangers on the tram to Docklands, she placed her capacious carpet bag on the seat next to her, then snapped open its sturdy Bakelite clip.

Rummaging inside among odds and ends, she felt for a knitted hat which she had abandoned more than a year ago after Miss Ball had rejected it.

‘My ladies could run that up in an hour,’ she had sniffed.

Cicely now smoothed it over her knee. Miss Ball had taught her that the knee and the back of the head were a similar form and size. Pulling the lilac cloche back into shape entailed parting her legs, so she was glad that she had chosen to wear her ankle-length tweed suit with its loose-fitting jacket concealing the skirt zip which wouldn’t quite close.

She wondered again if she should have braved giving a copy of Last Chance to Miss Ball when it had first appeared. Her name and her shop featured in it, though the interior life attributed to her may have offended her. It was too late now – years had passed, so it wou

ld have made a curiously tardy gift. Satisfied with the shape of the hat, she loaded the self-threading needle Miss Ball had introduced her to, then stuck it carefully in her lapel. She fumbled again in her bag and extracted a handful of knitted spiral flowers, from deep purple to pale mauve – an abandoned experiment in three-dimensional effects that had been gathering lint for more than a year. She bent over her needle, working furiously by feel rather than sight, intent on rejigging the plain hat with flowers that would bobble freely around the band.

This sudden compulsion to complete a vintage style hat was so strong that it enabled her to avoid dwelling on the possibility of a cold rejection upon her arrival at the flat.

Crochet was more manageable than knitting on public transport, but this simple trimming task was better than either. She had always taken public transport, using the time to read or do her handiwork. Even if she had been able to afford a car she imagined she might miss this productive travel time.

As she stitched, attaching each flower with relative ease, she prepared defensive topics of conversation, as timid people do. She would brush under the carpet the nightmare of those last days in the old share house, and try to be nice, even to Zac, by admiring the flat. She imagined being graced with a catch-up gossip. But his glowering face loomed up. She recalled their last phone conversation. Perhaps not.

If only Zac had not pointed out to Odette that Patchouli, in the novel, may have been based, ever so slightly, on her. Odette had not seemed to notice it before he had interfered.

She felt that recently she was stumbling along, shrinking from one cliff edge to another. Did Odette’s Tarot cards have anything to do with this disastrous reshuffling of their lives? It must simplify things to have that faith in the Tarot cards whenever life became insoluble.

Odette had used the Tarot cards ever since she was twelve, charging the girls at school a dollar for a reading. Later, at art college, it had gone up to ten dollars.

But Cicely had always resisted a reading from Odette, in keeping with her role of spectator on life. Instead of consulting them directly, Cicely had ended up reading and rereading Italo Calvino’s Castle of Crossed Destinies. Reading about the cards.

In his novel, pilgrims, like Chaucer’s, meet at an inn. They are unknown to each other. All are mute. To communicate with each other, to tell their life stories, they lay down the Tarot cards. Stories within a story. Their past lives are revealed to each other in the cards.

To be Odette, to act out in confidence the directions of the Tarot … Cicely herself was paralysed by forebodings that prevented such folly.

Attaching the last spiral flower using a stray magenta button as its centre, she just had time to cut the thread and store the completed cloche back in her bag before the tram jolted violently to its final stop.

She prayed that, by this visit, she could rescue her old relationship as expertly as she had rejigged that hat.

Intruder

Stepping carefully down from the tram, clutching at her red turban against the wind, Cicely had an attack of nerves.

So far out of her familiar surroundings, she was forced to confront how lost she was. How blurred her world seemed, like a painting by Turner, as she peered around the deserted streets of the once derelict wharf area. This suburb had sprung up overnight.

She had made, but failed to keep, three optometrist appointments, afraid of the diagnosis. Donning a peculiar pair of glasses instead of her usual cats-eyes, she checked a street name.

The specs were horn-rimmed, and in place of glass, had black cardboard pierced with tiny pinpricks. She had tried them out in the op-shop and to her surprise had found that they brought her world into relative focus, in a way that her old prescription glasses no longer did. She had seen ads in vintage magazines for these odd glasses, and wondered which eye defect they were correcting.

She slipped the glasses back into her deep, silk-lined jacket pocket. Zac and Odette had never seen her wearing them. She had thus succeeded in avoiding their pitying looks, escaping the ‘old’ Zac’s social-work lovemaking that she was sure would have followed if she had told him about her failing sight.

Her pride, in the end, had been the reason she had decided to sleep alone.

Across a gusty courtyard, she made out a café, deserted except for one resigned waiter smoking at an outside table. She smelt, rather than saw, the cigarette, and it may in fact have been a waitress, from this distance.

‘Golden Tower please?’ she asked, displaying the address printed on the key tag.

He stood and dramatically gestured behind him with his cigarette. There was the tower, its yellow walls glowing in the sunset. It gleamed like a lighthouse, leading her back, as it would, into the world of her friend.

Stepping anxiously towards it, she bumped into a giant succulent in an oversized pot. The waiter reached out his arms to stop her falling, and, in spite of his cloud of allergenic tobacco smoke that made her nose twitch, the warmth of that definitely male contact made her miss the arms of a living, breathing man.

The lobby door of Golden Tower pinged open, the only security two giant potted cabbage tree plants. Carefully, she skirted them. No one, as far as she could tell, in the lobby. Beige, cream and burnished metal everywhere.

No one in the lift either.

No one in the hall outside 510.

No answer when she knocked.

She was afraid of being arrested as a prowler, but reminded herself that if anyone accosted her, she had the stolen key with which she was now fumbling.

She cringed at the thought of how amusing she had once found the grandma in Absolutely Fabulous, with her magnifying sheet. Or Mr Magoo and other bumbling blind figures of fun, never suspecting that she had been destined to join their ranks. Mrs Magoo. No wonder the halt and the lame preferred to construct parallel universes of their own, where they could maintain a little dignity. Like them, she did not want to ask for help. Being an adult, was, after all, about doing things for yourself, and what every child dreamed of. She felt that there was no destiny for her but to live alone, for pity would be worse than mocking laughter.

She had assumed, however, that she would always have her best friend whenever she wanted her. After all, it had been Cicely, the loner, who had, up till now, set any limits necessary on intimacy.

Still no one answered her knock at the bright red door of 510, so she used the key, figuring out by trial and error the right angle, grateful that there was no witness to this new display of incompetence.

Finally, the door fell open, the duplicate key a very rough fit.

Cicely called her friend’s name.

No reply.

More nervously, she called Zac’s name.

Clues

Silence.

Stepping onto the soft beige carpet, she collided painfully with a brass casket just inside the door.

Losing her balance, she was sent sprawling. She rubbed her knee, assuming the genuflection position once familiar to her. With her other hand, she explored the esoteric symbols embossed on the lid of the box.

It was just big enough to contain a thin, flexible body, bent in two. Cautiously she opened it. The floor swayed under her feet as the scent of patchouli filled her nostrils.

But the velvet-lined box was empty.

She let the lid fall back again with a thud.

Dragging herself up from the floor, she stood and turned to the apartment, which still smelt of new carpet, fresh paint.

The floor was littered with packing cartons and paraphernalia from Odette’s studio. Plastic ice-cream buckets and ceramic containers, all encrusted with smeared terracotta and dried white stoneware clay. Turning tools, brushes and pots of glazes clustered around a wheel. Why had Zac so suddenly cleared out her studio just to store it here?

She dropped her carpet bag near the door and slipped off her white brogues, still shaped uncomfortably to some other woman’s foot. Using her hands to guide her, she began weaving her way between the mess and the cart

ons.

Catching her watercolour reflection in a mirror, she peered at it, drawn as she was by every mirror to test her vision. Would it be worse or miraculously better?

She had given up wearing make-up, as she was no longer confident of applying it properly – save a hopefully aimed slash of brown lipstick. She could make out only the podgy face, the flash of the scarlet turban.

For the first time, it struck her that her turban arrangement, inspired by de Beauvoir years ago, just would not do any more. She took it off. She knew exactly what should replace it.

Reaching into her carpet bag, she pulled out the newly trimmed cloche and slipped it over her hair. Its rather daring spiral flowers bounced jauntily just as she had imagined. Her head felt warm and protected and suddenly full of new energy.

The flowery creation matched so perfectly the way she was dressed today – the countrywoman’s tweed ensemble, and sensible brogues for walking the village streets of St Mary Mead waiting by the door.

She had felt driven to add this burgeoning garden to the hat, to wear it today, and now she knew why.

It was a hat that would have done even Miss Marple proud.

Her steady diet of Talking Books detective stories had subtly changed her. She realised that, just as ‘you are what you eat’, she was becoming what she was reading. Or hearing, to be precise.

What then was ‘her’ own brain? ‘Her’ own personality, if she could so easily become the main character in whatever book she was ingesting?

Yet it had taken more than a single book, more even than three or four. She must have read or listened to the entire output of Christie’s words about Miss Marple. So many stories that she had lost count.

She was ruined for serious literature now, she was sure.

If she ever picked up a Virginia Woolf again, she would be always waiting for the murder that would never take place.

She pulled the comforting cloche further down over her ears and turned back to her investigations.

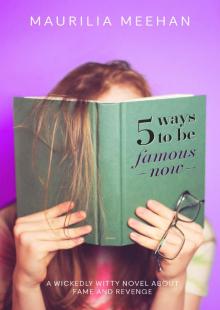

5 Ways to be Famous Now

5 Ways to be Famous Now Madame Bovary's Haberdashery

Madame Bovary's Haberdashery